Al Feldstein died the week before last on Tuesday, April 29. The obituaries I’ve seen since then focus mainly on his association with Mad magazine, which he edited for 29 years, from 1956 to 1985. Mad is likely to be what he’ll be most remembered for, but what I think of first is the incredible work Feldstein did with the EC horror, crime, and science-fiction comics during the early 1950s. According to Wikipedia, Feldstein started at EC in 1948, where he “began as an artist, but soon combined art with writing, eventually editing most of the EC titles. Although he originally wrote and illustrated approximately one story per comic, in addition to doing many covers, Feldstein finally focused on editing and writing, reserving his artwork primarily for covers. From late 1950 through 1953, he edited and wrote stories for seven EC titles.”

Al Feldstein died the week before last on Tuesday, April 29. The obituaries I’ve seen since then focus mainly on his association with Mad magazine, which he edited for 29 years, from 1956 to 1985. Mad is likely to be what he’ll be most remembered for, but what I think of first is the incredible work Feldstein did with the EC horror, crime, and science-fiction comics during the early 1950s. According to Wikipedia, Feldstein started at EC in 1948, where he “began as an artist, but soon combined art with writing, eventually editing most of the EC titles. Although he originally wrote and illustrated approximately one story per comic, in addition to doing many covers, Feldstein finally focused on editing and writing, reserving his artwork primarily for covers. From late 1950 through 1953, he edited and wrote stories for seven EC titles.”

William M. Gaines became the publisher and co-editor of the EC line after his father, M.C. Gaines, was killed in a speedboat accident. EC originally stood for Educational Comics (later Entertaining Comics), which were best known for illustrated adaptations of Bible stories, as well as subjects such as world history and science. There’s a certain irony to that, given what came after. According to Feldstein, the elder Gaines was “losing his shirt, so he had to start putting out crime books and Western books. That’s what Bill inherited.”

The covers for these comics are what I would have remembered when I was a kid in the 50s. My dad was pretty strict about keeping me away from material like this. Superman and Batman were okay, but the closest I usually got to comics like Tales from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror was seeing them in magazine racks at news stands and drugstores. The covers were great and really fired my imagination, though of course I didn’t have any idea who the artists were. I also didn’t have a deep exposure to these comics until the mid-80s, when I started buying boxed-set reprints of all the EC titles. It was too late by then to turn me into the dope fiend and juvenile delinquent punk I obviously would have become had I started reading them earlier, though they probably set me back a few years anyway.

Here are two covers by Feldstein that reflect his distinctive style.

The Weird Science cover above has a fairly juvenile sensibility, though no less engaging for that. This is the one I would have responded to at the time, more so than the Shock SuspenStories cover, which is something different altogether. How many comic books in the 1950s would showcase a depiction of drug addiction as graphic as this cover does? Per the Wikipedia entry on Feldstein, “In creating stories around such topics as racial prejudice, rape, domestic violence, police brutality, drug addiction and child abuse, he succeeded in addressing problems and issues which the 1950s radio, motion picture and television industries were too timid to dramatize.” Tackling these subjects within the comic book context of horror, crime, and science-fiction seems subversive in retrospect, and that’s not a criticism. This was probably also a motivating factor in the Congressional investigation of the comics industry a few years later.

The Weird Science cover above has a fairly juvenile sensibility, though no less engaging for that. This is the one I would have responded to at the time, more so than the Shock SuspenStories cover, which is something different altogether. How many comic books in the 1950s would showcase a depiction of drug addiction as graphic as this cover does? Per the Wikipedia entry on Feldstein, “In creating stories around such topics as racial prejudice, rape, domestic violence, police brutality, drug addiction and child abuse, he succeeded in addressing problems and issues which the 1950s radio, motion picture and television industries were too timid to dramatize.” Tackling these subjects within the comic book context of horror, crime, and science-fiction seems subversive in retrospect, and that’s not a criticism. This was probably also a motivating factor in the Congressional investigation of the comics industry a few years later.

Feldstein elaborates on the improvised way he and Gaines worked in an excellent career-spanning interview conducted by Jason Heller in the A.V. Club section of The Onion in 2007: “One day (Bill Gaines) came in and slapped two pulp magazines on my desk, and he said, ‘What do you know about science fiction?’ I said, ‘Absolutely nothing.’ And he said, ‘Well, I love it. Take this home and read it.’ I came back to Bill — greedy little me, I was a whore — and said, ‘I can write this stuff.’ (Laughs.) So we started putting out Weird Science and Weird Fantasy. Then we got into the political aspect of our society at the time: the fact that we had racial intolerance, anti-Semitism. What we went to World War II for, at least in my mind, was not getting taken care of. It was supposed to be a brave new world, but we were getting back into the old ruts, and we were in a cold war with Russia. We started this title called Shock SuspenStories, because it had these shock endings. Bill labeled them ‘preachies’ — they were stories that had to do with racial intolerance, politicians, corruption.”

Years before he started at EC, Feldstein, at age 15, began working in the Eisner & Iger studio, which was begun by Will Eisner, creator of the great Spirit comic books. Eisner had left the studio by then, but Jerry Iger gave Feldstein a job running errands and cleaning up pages for $3 a week. He was eventually given the opportunity to work on the Sheena Queen of the Jungle comic, painting leopard spots on Sheena’s top and loincloth. This awesome effort was his first published artwork.

Feldstein then spent some time in the Special Services branch of the Army Air Corp during World War II, where (per Wikipedia) he gained experience “creating signs and service club murals, decorating planes and flight jackets, drawing comic strips for field newspapers and painting squadron insignias for orderly rooms.”

After his discharge, Feldstein began working for Fox Comics, where he wrote and drew two comic series called Junior and Sunny. I was somewhat amazed to find these rather jaw-dropping covers by Feldstein, both of which are extremely suggestive. Or is it just me?

Feldstein soon left Fox Comics to join Bill Gaines, with whom he worked with at EC for the next 35 years. It was during his tenure that EC began running into trouble in the early ’50s with organizations and parents concerned about the effect these comics were having on young

Feldstein soon left Fox Comics to join Bill Gaines, with whom he worked with at EC for the next 35 years. It was during his tenure that EC began running into trouble in the early ’50s with organizations and parents concerned about the effect these comics were having on young

people. Frederic Wertham, a German-American psychiatrist, was the leading proponent of the belief that this effect was seriously negative, and contributed to juvenile delinquency, a hot-button topic at that time. His book, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth (1954), got serious attention and added to the growing alarm among parents and civic groups. At the time I remember getting a copy from either the school library or one of our local public libraries and reading it several times. What I don’t remember is why I read it more than once, or what I got out of it. It certainly didn’t dissuade me from reading comics. I think it may have interested me that a book had been written about comics and was treating them seriously, even though it was attacking them, which I clearly chose to ignore. (The photo above left shows Dr. Wertham at work, probably appalled by what he’s seeing. He does not look like an especially fun guy, and definitely not someone likely to appreciate comics with titles like Weird Science and The Haunt of Fear. Or any comics, really.)

people. Frederic Wertham, a German-American psychiatrist, was the leading proponent of the belief that this effect was seriously negative, and contributed to juvenile delinquency, a hot-button topic at that time. His book, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth (1954), got serious attention and added to the growing alarm among parents and civic groups. At the time I remember getting a copy from either the school library or one of our local public libraries and reading it several times. What I don’t remember is why I read it more than once, or what I got out of it. It certainly didn’t dissuade me from reading comics. I think it may have interested me that a book had been written about comics and was treating them seriously, even though it was attacking them, which I clearly chose to ignore. (The photo above left shows Dr. Wertham at work, probably appalled by what he’s seeing. He does not look like an especially fun guy, and definitely not someone likely to appreciate comics with titles like Weird Science and The Haunt of Fear. Or any comics, really.)

Due in no small part to the alarm created by Wertham’s book, a U.S. Congressional inquiry into the comic book industry was held in 1954. The investigation especially focused on EC Comics, which were more artistic and imaginative than just about anything else on the market, and this, if anything, made them that much more dangerous to the powers that be. EC’s sensationalistic approach frequently left good taste (however that’s defined) in the dust, making it an easy target (along with rock ‘n’ roll and Elvis Presley) for proponents of decency and morality. William Gaines’ testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency didn’t help his cause, nor did covers like the three below, drawn by Johnny Craig. They’re pretty extreme, but I have to say, living in New York City and being a frequent subway rider, I get a big kick out of this The Vault of Horror cover.

The cover at right became a flashpoint for Senate Subcommittee members. My original plan was to position it just below The Vault of Horror cover above, and in the same size. The more I looked at it at that scale, the more I thought, “Man, this is just too much, it’s overwhelming.” So I had a failure of nerve and reduced the size to what you see here. By comparison, the rather meta cover at left, with a maniac (one assumes) wielding a straight razor as he attacks (by implication) the person holding the comic, seems somehow more acceptable. Whew.

The cover at right became a flashpoint for Senate Subcommittee members. My original plan was to position it just below The Vault of Horror cover above, and in the same size. The more I looked at it at that scale, the more I thought, “Man, this is just too much, it’s overwhelming.” So I had a failure of nerve and reduced the size to what you see here. By comparison, the rather meta cover at left, with a maniac (one assumes) wielding a straight razor as he attacks (by implication) the person holding the comic, seems somehow more acceptable. Whew.

How does one defend this kind of material? It’s not easy. It’s like you’re either tuned into  this sensibility or you’re not. Gaines tried his best to defend and explain it, but failed, and was demonized in the national media. The result was the creation of the Comics Code Authority, which effectively drove EC out of business, except for one title, and that title was Mad. Harvey Kurtzman had joined EC in 1950 and had already established himself with his realistic war comics, Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat, when he created Mad in 1952, writing most of the first issue and illustrating it, along with EC stalwarts Wally Wood, Will Elder, and Jack Davis, three artists who came to define the Mad‘s visual style.

this sensibility or you’re not. Gaines tried his best to defend and explain it, but failed, and was demonized in the national media. The result was the creation of the Comics Code Authority, which effectively drove EC out of business, except for one title, and that title was Mad. Harvey Kurtzman had joined EC in 1950 and had already established himself with his realistic war comics, Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat, when he created Mad in 1952, writing most of the first issue and illustrating it, along with EC stalwarts Wally Wood, Will Elder, and Jack Davis, three artists who came to define the Mad‘s visual style.

Mad was a comic book for 23 issues until 1955, when Gaines changed it to a magazine format, mainly to avoid the restrictions of the Comics Code. Kurtzman continued as editor for another year, when Al Feldstein took over in ’56. Feldstein edited Mad for the next 28 years, until 1984.

It was during Feldstein’s tenure, especially in the 60s, that I became a loyal Mad reader. Feldstein’s first issue as editor was also the first to showcase the incredible work of  Don Martin. Martin’s distinctive way of rendering figures became a signature feature of the magazine. (I wish I still had the first paperback collection of his strips for Mad.)

Don Martin. Martin’s distinctive way of rendering figures became a signature feature of the magazine. (I wish I still had the first paperback collection of his strips for Mad.)

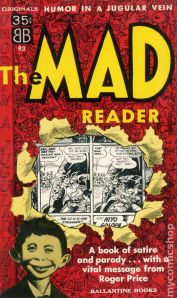

But the signature feature of Mad has to be Alfred E. Neuman. His distinctive image had been around for years, with sightings dating back to 1894. He made his first official Mad appearance on the cover of The Mad Reader, a paperback collection of material from the first two years of the comic published by Ballantine Books in 1954. This and the many subsequent collections (Utterly Mad, The Brothers Mad, etc.) were my first exposure to what had appeared in the original Mad comic. They were proud possessions in my library for years, becoming increasingly worn and frayed, until at some point they disappeared entirely.

As Wikipedia puts it, after becoming editor of Mad in ’56, Feldstein “seized upon the face.” Per Feldstein: “I decided that I wanted to have this visual logo as the image of Mad, the same way that corporations had the Jolly Green Giant and the dog barking at the gramophone for RCA. This kid was the perfect example of what I wanted. So I put an ad in the New York Times that said, ‘National magazine wants portrait artist for special project’. In walked this little old guy in his sixties named Norman Mingo, and he said, ‘What national magazine is this?’ I said ‘Mad’, and he said, ‘Goodbye.’ I told him to wait, and I dragged out all these examples and postcards of this idiot kid, and I said, ‘I want a definitive portrait of this kid. I don’t want him to look like an idiot—I want him to be loveable and have an intelligence behind his eyes. But I want him to have this devil-may-care attitude, someone who can maintain a sense of humor while the world is collapsing around him.’ I adapted and used that portrait, and that was the beginning.” Mingo went on to paint a total of 97 Mad covers, all of which feature Alfred E. Neuman.

As Wikipedia puts it, after becoming editor of Mad in ’56, Feldstein “seized upon the face.” Per Feldstein: “I decided that I wanted to have this visual logo as the image of Mad, the same way that corporations had the Jolly Green Giant and the dog barking at the gramophone for RCA. This kid was the perfect example of what I wanted. So I put an ad in the New York Times that said, ‘National magazine wants portrait artist for special project’. In walked this little old guy in his sixties named Norman Mingo, and he said, ‘What national magazine is this?’ I said ‘Mad’, and he said, ‘Goodbye.’ I told him to wait, and I dragged out all these examples and postcards of this idiot kid, and I said, ‘I want a definitive portrait of this kid. I don’t want him to look like an idiot—I want him to be loveable and have an intelligence behind his eyes. But I want him to have this devil-may-care attitude, someone who can maintain a sense of humor while the world is collapsing around him.’ I adapted and used that portrait, and that was the beginning.” Mingo went on to paint a total of 97 Mad covers, all of which feature Alfred E. Neuman.

Under Al Feldstein, Mad became hugely successful, with circulation increasing more than eight times after he became editor, reaching a peak of 2,850,000 in 1974. It also became a much-loved institution. I especially liked the movie and TV parodies. An example of the affection that was felt for the magazine can be seen in an episode of The Simpsons titled “The City of New York vs. Homer Simpson” (airdate September 21, 1997), which had the distinction of being pulled from syndication after 9/11 because the World Trade Towers figure prominently in the storyline. Near the end of this episode, Bart visits the office of Mad magazine. He’s initially disappointed when it seems like just an ordinary office, but then a door opens and Alfred E. Neuman leans out, with all sorts of Mad shenanigans visible in the room behind him. Bart proclaims he will never wash his eyes again. It’s a lovely grace note in the episode.

Feldstein retired from Mad in 1984, left Connecticut and moved to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and eventually to Paradise Valley, Montana, near Livingston. During this time he began painting again. It’s ironic, and even a little weird, that his subjects were landscapes and wildlife, worlds away from the grotesque and often shocking covers he did for EC.

Al Feldstein, October 24, 1925 (Brooklyn, New York) to April 29, 2014 (Livingston, Montana). 88 years of age. He left his mark and then some. Rest in peace, Al. — Ted Hicks

A wonderful essay/obit. Thank you for filling in the spaces… we so often only know someone because of their One Big Thing.

Pingback: Movie Tie-Ins: Novelizations & Comic Books | Films etc.