I saw this recently as part of Film Forum’s 3-week series of films written and directed by Billy Wilder (July 14 to August 3). Double Indemnity (1944) is one of the greatest film noirs ever made. Though at the time, no one referred to the films that have come to be known as film noir by that name. The term was first coined by French critic Nino Frank in 1946 to describe certain Hollywood films. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the term became widely used in this country.

I saw this recently as part of Film Forum’s 3-week series of films written and directed by Billy Wilder (July 14 to August 3). Double Indemnity (1944) is one of the greatest film noirs ever made. Though at the time, no one referred to the films that have come to be known as film noir by that name. The term was first coined by French critic Nino Frank in 1946 to describe certain Hollywood films. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the term became widely used in this country.

In the Spring 1972 issue of Film Comment, an important article by future film director Paul Schrader appeared titled “Notes on Film Noir.” It opens with this: “In 1946 French critics, seeing the American films they had missed during the war, noticed a new mood of cynicism, pessimism and darkness which had crept into American cinema. The darkening stain was most evident in routine crime thrillers, but was also apparent in prestigious melodramas.”

There’s still a debate about among film critics and historians as to whether film noir is a distinct genre or is it a filmmaking style? Whichever, I know it when I see it. And Double Indemnity is definitely it.

________________________________________________

The plot is Film Noir 101. Ordinary guy Walter Neff, an insurance salesman, meets bored housewife Phyllis Dietrichson. They conspire to kill her husband for the insurance money. Phyllis is a scheming femme fatale. Walter is a wise-cracking cynic, but weak and out of his depth. Big surprise: it doesn’t work out. As Neff says in a Dictaphone confession to Barton Keyes, his friend and mentor and the company’s claims adjuster, “I killed him for money…and for a woman. And I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman.” These words sum up how things work out for most noir protagonists.

_______________________________________________

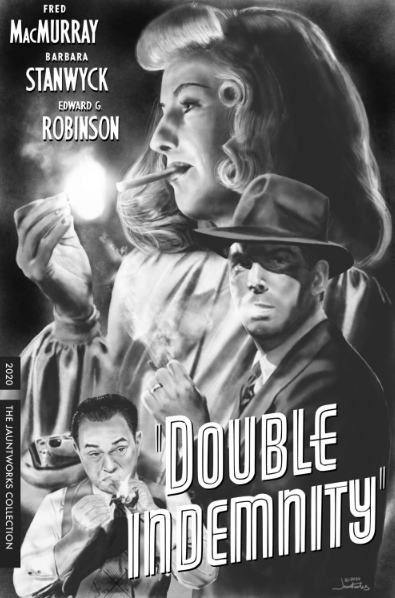

Barbara Stanwyck was Wilder’s first choice to play Phyllis Dietrichson. At the time, she was the highest-paid actress in Hollywood. Fred MacMurray, who was eventually signed to play Walter Neff, was the highest-paid actor in Hollywood in 1943. Wilder had trouble casting the Neff role. Reportedly, actors who turned it down included Alan Ladd, James Cagney, Spencer Tracy, Gregory Peck, and Frederic March. Per Wikipedia: “Wilder finally realized that the part should be played by someone who could not only be a cynic, but a nice guy as well. Fred MacMurray was accustomed to playing ‘happy-go-lucky good guys’ in light comedies, and when Wilder first approached him about the role, MacMurray said ‘You’re making the mistake of your life!’ MacMurray made a great heel and his performance demonstrated new breadths of his acting talent. ‘I never dreamed it would be the best picture I ever made,’ he said.”

Stanwyck, MacMurray, and Edward G. Robinson as Barton Keyes, the company’s claims adjuster and Neff’s friend and mentor, were at the top of their game in this film. Robinson is especially good. Watch him in this scene where he’s gone to Walter’s apartment to talk out his suspicions.

____________________________________________

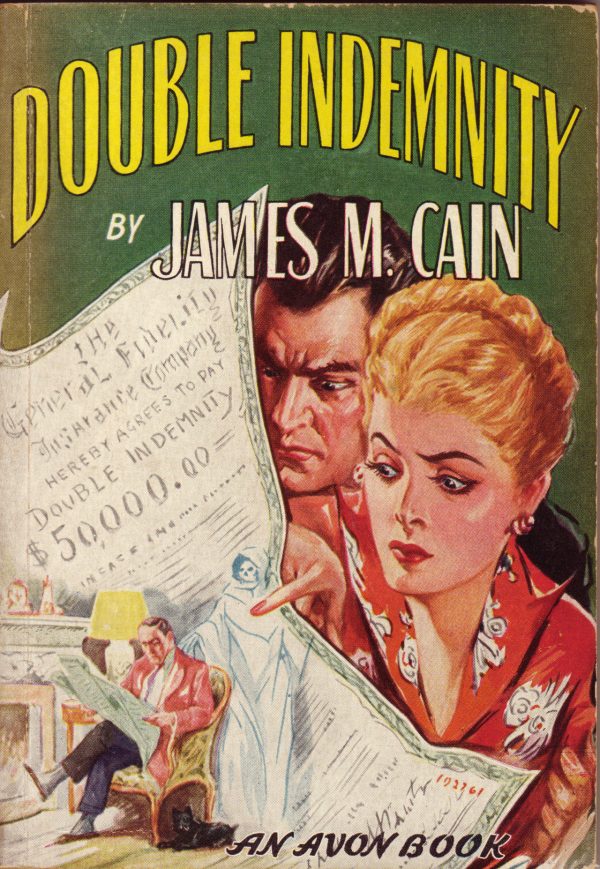

Double Indemnity was based on James M. Cain’s 1943 novel. Here are covers for some of the editions. I particularly like the first one.

Note that the cover at left replicates the following scene from the film.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Double Indemnity was scored by Miklós Rózsa, who had done the music for Wilder’s previous film, Five Graves to Cairo (1943). Wilder had liked his work and wanted to use him again. Rózsa went on to score a number of significant film noirs, including The Killers (1946), Brute Force (1947), The Naked City (1948), Criss Cross (1949), and The Asphalt Jungle (1950). He wrote music for many other films, such as Ben-Hur (1959) and El Cid (1961). His music for Double Indemnity is powerful and ominous. You can hear it accompanying this main title sequence, which leads into the first scene of Walter arriving at the insurance company building.

_______________________________________________

Double Indemnity was co-written by Wilder and Raymond Chandler. Chandler was a novelist new to Hollywood, but had already written The Big Sleep (1939), Farewell My Lovely (1940), and The Lady in the Lake (1943). They reportedly had a contentious relationship. Per Wikipedia: “To help guide him in writing a screenplay, Wilder gave Chandler a copy of his own screenplay for the 1941 Hold Back the Dawn to study. After the first weekend, Chandler presented 80 pages that Wilder characterized as useless camera instruction’; Wilder quickly put it aside and informed Chandler that they would be working together, slowly and meticulously. By all accounts, the pair did not get along during their four months together. At one point Chandler even quit, submitting a long list of grievances to Paramount as to why he could no longer work with Wilder. Wilder, however, stuck it out, admiring Chandler’s gift with words and knowing that his dialogue would translate very well to the screen.”

There’s a very short scene early in the film where Chandler is seen sitting in a chair outside Keyes’ office as Walter leaves. Apparently, very little film exists of Chandler in any capacity, so this is an interesting cameo.

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

The original ending to Cain’s novel has Walter and Phyllis committing double suicide, one of the many aspects in the book forbidden at the time by the Motion Picture Production Code. Wilder wrote a different ending with Walter going to the gas chamber as Keyes watches. Per Wikipedia: “This scene was shot before the scenes that eventually became the film’s familiar ending, and once that final intimate exchange between Neff and Keyes revealed its power to Wilder, he began to wonder if the gas chamber ending was needed at all. ‘You couldn’t have a more meaningful scene between two men’, Wilder said. He later recounted: ‘The story was between the two guys. I knew it, even though I had already filmed the gas chamber scene … So we just took out the scene in the gas chamber,’ despite its $150,000 cost to the studio. Removal of the scene, over Chandler’s objection, removed Production Code head Joseph Breen’s single biggest remaining objection to the picture that regarded it as ‘unduly gruesome’ and predicted that it never would be approved by local and regional censor boards. The footage and sound elements are lost, but production stills of the scene still exist.” Below is one of the surviving stills of the discarded scene.

__________________________________________

__________________________________________

Here is the scene Wilder opted to end with. It is intimate and powerful, with a great deal of feeling. When Keyes says, “Closer than that, Walter,” it’s very moving, a heartbreaking punch to the gut.

___________________________________________

Several times in the film, Walter and Phyllis state their commitment to each other and their plan to kill her husband by saying, “Straight down the line.” Of course, it turns out their line gets pretty crooked, not so straight. Here are two clips where we hear this. In the first, longer clip, the plan is hatched. (There’s a detail in this clip that I love. At the end, after Phyllis leaves Walter’s apartment, as he walks across the room he notices the corner of a rug flipped over. He pauses to flip it back with his foot. This is a totally ordinary, inconsequential detail, one that feels very real because of that.)

___________________________________________

Double Indemnity was nominated for seven Academy Awards in 1945, including one for cinematographer John Seitz, whose many credits, dating back to the silents, include The Lost Weekend (1945), Sunset Boulevard (1950), A Place in the Sun (1951), and Invaders from Mars (1953). His “venetian blind” lighting, with rays of light slashing through a room, creating angled bars of light and dark, became a standard look, and eventual cliché, for film noir and neo-noir.

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

For my money, Double Indemnity is as close to perfect as you can get. It’s beautifully written, performed, and filmed. All the pieces matter, and all the pieces fit.

I think that about wraps it up. Stay safe. See you next time. – Ted Hicks

_________________________________________________

Well done, Ted.

Tis is an informative ad enjoyable blog of an important film.